Leaving Well Enough Alone

by Paul Hyett

PPRIBA, Hon FAIA

Founding Principal of Vickery-Hyett in the U.K.

May 17, 2023

Paul Hyett examines contexts and agendas in UK housing.

Two Contexts

Context is everything for architecture, and two kinds of “contextual” agendas shape

its progress.

The first is the corporeal context – i.e., the physical, the tangible and the palpable, that which exists at the outset. Think of it as the “landscape,” the materials and the technologies within which, and from which, we shape our work. Whether urban or rural, no architecture of worth can but respond to its corporeal context.

The second is the incorporeal context – that which has no material structure or existence. Here lie the common yet dynamic customs and values that combine to provide the culture and quotidian backdrop of the citizens’ lives.

I want to focus herein on the extraordinary impact this latter, essentially cerebral, form of contextual awareness can have on domestic architectural work during its conception and thereafter in the minds of residents as they reshape such buildings in response to their current needs and ambitions.

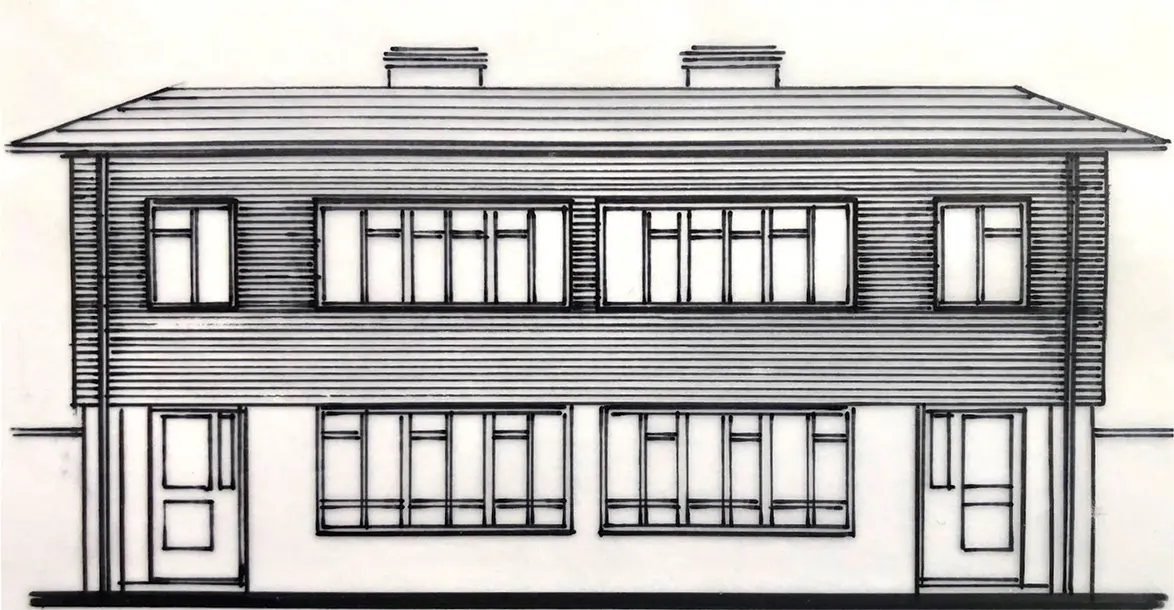

Image 1: Sir Frederick Gibberd’s British Iron and Steel Federation prefabricated house, author sketch, source: https://nonstandardhouse.com/the-british-iron-steel-federation-bisf-house/

Come the Modern

Take the sketch above:

I see this design as breathtakingly and unequivocally modern. To my mind, it should be preserved (rather than defiled) as a symbol of both hope and confidence in technology to create a brighter, cleaner, healthier and happier tomorrow. That was, after all, the prevailing incorporeal context in which such work was originally developed and delivered: A nation recovering from seven long, hard years of war believed in such a future.

Designed by Frederick Gibberd, this pair of semidetached houses was one of a series of projects commissioned by the British government during the Second World War in anticipation of the extensive repair work that would be required to our heavily bombed cities. But there was also a bigger agenda: The Homes for Heroes campaign at the end of World War I had offered much in the way of progress, but the New Jerusalem movement of the ’40s was concurrently demanding still more for a population that had suffered and given so much to the war effort.

The corporeal reality was all too stark: Slums comprising mile upon square mile of high-density Victorian housing – many with no internal toilets – were to be cleared and replaced. Particularly obscene to the liberal philanthropists who led the campaign were those comprising back-to-back housing, with only communal sanitation at the street ends. They all had to go, and amongst many such initiatives, Gibberd would work with the British Iron and Steel Federation (BISF) to create the BISF House, a revolutionary form of construction that proposed to repurpose those factories hitherto dedicated to the supply of military planes, vehicles and ammunition towards peaceful production.

So, out with old-fashioned, load-bearing brickwork and traditional on-site construction techniques, all part of a building typology associated with damp conditions, death in childbirth, high rates of infant mortality, disease and tuberculosis, and in with efficient, steel-framed, modern system building as epitomised by Gibberd’s new model homes and sophisticated factory manufacturing processes.

One of the most important aspects of this new housing would be its form of tenure. Local authorities, who had intervened to provide the new and better housing of the pre- and post-World War I building programmes, would be invited (and funded by central government), to up their games and offers: As part of a new social contract, low-rent housing would be maintained by the authorities to the highest of standards.

The reciprocal obligations of the deal were simple: Families would pay their rents, keep the properties clean and the gardens tidy, whilst the council would ensure the structure and external fabric were kept in good decorative repair. For several decades, this all worked well. Tenants acknowledged that their homes were but a small part of estates that would remain of uniform character: collections of terraced and semi-detached houses assembled into larger compositions of consistent architectural integrity. In turn, such consistency relied upon the occupants’ acceptance that the outsides of their homes would remain unchanged.

I grew up in one such home, and my parents weren’t even allowed to repaint the front door.

Cultural and Social Contracts

So, there we have it: Residents were fully cognisant of, and submissive to, the fact that within the corporeal context there was an inevitable enduring “sameness” to their homes. This was the norm. What else would anyone expect? The underlying assumption was: Why should such homes, as part of an estate comprising hundreds of other family dwellings, have anything but a constancy of character?

Which takes us to the evolving incorporeal context — that is, those cultural characteristics manifest in the abstract identity of a community. The so-called social contract of the post-World War II era would be challenged in the ’80s with the arrival of the Thatcher governments. Community values and expectations would consequently change in a way that would have profound and, in my view, extremely damaging impact on these brave new architectures of the post-WWII era.

The mechanism of change would be the subsidised “right to buy” programmes. These were based on a powerful new central government ideology that would force local authorities to sell their housing stock to those tenants wishing to buy. So ideologically committed were the political leaders to this agenda they promoted a systematic, covert campaign to discredit municipal housing: Step by grim step, it came to be perceived as a provision for the unfortunate and the needy within the community. Dignity and renting from the council would become mutually incompatible.

With this came the destruction of that incorporeal contextual awareness and respect that had so effectively preserved and protected the new architectures of municipal housing, specifically tenants who had proudly identified themselves with a status of being part of a manifest community whose character was as much incorporeal as it was corporeal.

Under Mrs. Thatcher, everything that could be sold was sold, and tenants were encouraged to buy their homes at knock-down prices. Which is what they did. The result? Of some 5 million council homes that existed in Britain by 1980, following a building boom that had seen an average of 126,000 homes built annually since 1945, some 1,700,000 (34%) would be sold by 1997. And they have gone on selling them ever since.

Here’s the point: This policy has had the most astonishing and profound consequences and impact on our population in the incorporeal territory of its individual and collective character. Through that process, it has also deeply affected the corporeal character of the built fabric within which they now live.

Inappropriate Interventions

The images below illustrate the issues. Image 1 displays typical municipally built and rented properties presale, all well-maintained under state ownership in a manner that preserves the overall design integrity of the estate.

Images 2 and 3 were taken by me during a recent tour of a post-war estate at Debden, northeast London:

I don’t question the ambition, intention or pride manifest in the work some of the new owners have carried out whilst personalising these properties, but their disregard for any obligation or contribution to the character of the whole is extraordinary, if not shocking.

It gets worse, as the photographs below show. Clearly, one of the finest post-World War I estates in west London, the Old Oak Estate, has also been a victim of the “right to buy” policy. I quote from a recent article I wrote for World Architecture Foundation magazine:

Image 2, 3: Debden housing, author photos

“It seems that an awful pox has enveloped large parts of the housing stock of our nation. Across the entire land, be it large city or small town, older Victorian stock, or the newer housing estates of the early and middle 20th century, that pox is everywhere to be seen. Indeed, barely a street has been spared.”

“Much of this takes the form of additions, be they new front porches, side additions, or the mutilation of roof lines to accommodate attic extensions. But window and front door replacements; new facias, soffits, gutters and downpipes; new plastic weatherboarding; and the frequent introduction of stone cladding, pebble-dash renders, or simply paint to what were originally traditional brick facades have also taken their toll and added to the visual dross that now surrounds us. And all that takes no count of the stripping away of finials and ridge tiles, the cheap and nasty plastic car-ports, the damage to fences, gateways, hedges and the like, or the sacrifice of front gardens to car parking.”

“Tragically, much of this havoc has been wreaked on some of the finest housing stock in existence. For example, at the Old Oak Estate in Hammersmith which has been described as the ‘culminating achievement of the (London County) Council’s venture into garden suburb planning before the first world war.’”

“The two photographs below, both contemporary and taken on the same day, well illustrate the point. Showing adjacent quadrangles of housing set back off Mellitus Street, the first shows the properties mercifully relatively intact in terms of appearance. Only the base of the gable wall adjoining the street pavement has been ‘damaged’ through the addition of red paint to the brickwork.”

Image 4: Mellitus Street quadrangle with architectural integrity preserved, author photo

“The second photograph tells an entirely different story: a virtually identical architectural composition, the end property has been rendered, thus concealing its fine brickwork, and the third and fourth properties have been respectively rendered, painted, and clad in imitation stone.”

“And it does not stop there! Apart from being replaced with plastic windows, the window openings, and thus their proportions, have been re-configured to the end house, the transom and mullion arrangements have been varied, and a crude array of drainage pipes have been added. All in all, the architectural homogeneity of the original composition has been so heavily compromised that it is all but lost.”

Image 5: Mellitus Street adjoining quadrangle with architectural integrity seriously undermined as a consequence of the “right to buy” programme, author photo.

The conclusion to all this is tragic. Somehow, against an ever-growing emphasis on individualism and self-expression, and against several decades of the British state shunning its responsibility to provide and maintain well-designed homes as part of our national infrastructure, extraordinary damage to the corporeal fabric – and to the incorporeal culture of our communities – has taken place.

And it has all gone virtually unnoticed.

Sad indeed.

Paul Hyett is the founder of Vickery Hyett Architects, past president of the RIBA and a regular contributor to DesignIntelligence.