The Case for the Misfit

by Ella Hazard

Managing Director, Arktura Ventures

November 30, 2022

Ella Hazard explains: the “who” is the “how”

I’ll start with a recent chat from my personal life regarding some great progress I’d made at work:

“But are you finding the same caliber of candidate?” this person inquired.

“Wait, what do you mean? I’m not sure I understand?” I replied.

“Well, you know, the same skill sets and qualifications ... are they comparable?” was the response.

“Comparable to what? No, these candidates aren’t comparable, but better! Also ... who are they, and why are you asking this?”

As a manager in a hiring push, doing her darndest to build a great team, I was confused. And curious. Excited to bring together a diverse group of people who would successfully bridge research insights, design and meaningful innovation, I noticed that when “representation” entered the conversation, it drew a skeptical response (like this one, from a close, personal connection). It often does.

In these times, and with all we know about the business case for diversity,1 I wondered why.

“Meaningful” innovation can manifest in several ways: by being novel, powerfully insightful, well-loved, broadly adopted or financially significant. None of these qualities are mutually exclusive. In fact, when you achieve many of these conditions at the same time is usually when you have a hit. The missing aspect, few seem to understand, is how nuanced, complex and purpose-hungry consumers are becoming. To understand them, you literally have to be them.

Here’s my hypothesis: In a human-centered approach, not only does the research need to reflect the target, the team does, too.

As creators, designers, architects and planners, we’ve long held the privilege and responsibility of helping shape the world we live in and with which we contend. It’s my opinion that the best among us have learned to adopt a research-based approach, one that takes a traditionally linear process and closes the loop to engage with occupant feedback. It helps when we stop assuming we got it right and check our work with those who experience it most intimately. This way of thinking positions occupants as the source of the research and dictates that the constitution of the creating team should represent the end user in as many nuanced facets as possible.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to enter conversations with the built environment and its inhabitants by admitting that, though we try our best, not every outcome is as intended? To understand it’s better to learn through the process of getting something a little bit wrong — in real time, together — about how to make it right?

Enter “the misfit.” The fringes, the nonconformists, the untraditional and the neither-here-nor-there’s of the world. I believe they can uniquely help us navigate the inherent ambiguity that reframing our role and approach to feedback requires.

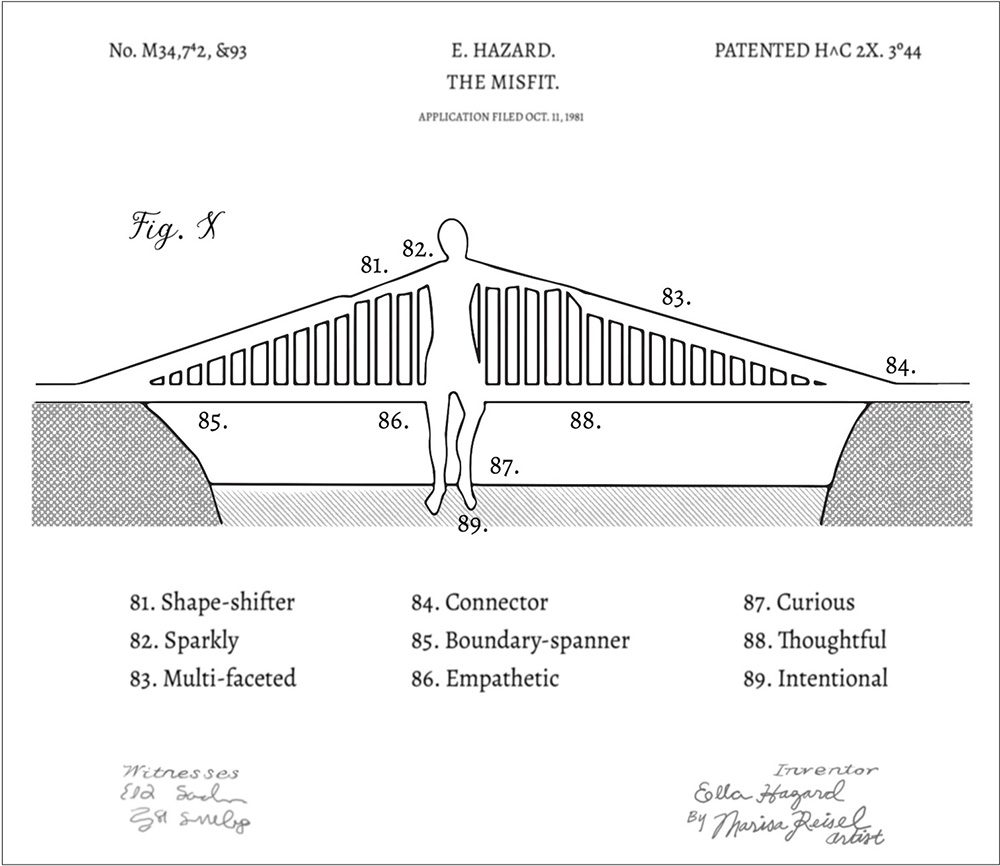

“The Misfit,” Conceptual illustration by Marisa Reisel

Misfits Defined

Full disclosure: I’m a misfit myself. A sparkly, mixed-race kid from a one-stoplight town. I’m someone who’s spent a lot of time on the outside looking in, shape-shifting to meet others where they are. I can belong both nowhere and everywhere at once. Glue comes to mind, seeping where needed to fill the cracks.

Misfits like me know that observation and empathy are key to survival. I’ve learned, too, that nonconformity can be a strength when wielded with agency and the preservation of one’s deep-rooted sense of self.

I stand by the power of the misfit, not for my own future job security but because of what I’ve seen in the past. That conviction comes from failure. Lots of failure — different flavors, varieties and magnitudes of failure. On the other side of it all, one clear insight stands out: It’s not the concept that matters, but the people. A mediocre idea pursued by a great team has better odds of success than an amazing idea with a mediocre team.

Good Teams/Bad Teams

To understand what makes a good team, it might be helpful to understand what makes a bad one. What looks like a great team from the outside often doesn’t function well on the inside. The most insidious version of teaming I’ve experienced is what I’ll call “The All-Star Team” — a grouping of professionals who individually sit at the top of their respective fields. This is the nightmare of all nightmares, a team of specialists sought out to “know” things is rarely the right group to ask good questions, “suppose” together or say dumb stuff in front of one another.

This isn’t always the case, but I would be much more interested in the conversation between the junior contributors in those same fields who may be more willing to freely discuss what they want to do and what is possible as a group, rather than what they know and have already done.

Francesca Gino describes a counterintuitive approach in her book “Rebel Talent: Why it Pays to Break the Rules at Work and in Life.” She outlines the threats of domain expertise to innovation, the case for championing “the outsider” and, as I read it, the notion that those with nonlinear career paths may have more to offer. What I take from her counsel is that we should begin to see this kind of candidate as a positive in certain roles and stop opting for the “safe” choice every time.

Another leading voice in the space, author Erin Meyer, explains how our expectations and styles will vary based on the places from which we come.2 She argues for anticipating these cultural biases and working harder to understand ourselves — and each other — to break down communication barriers.

A final reference I return to often is “Range” by David Epstein. In the book, he warns us that in our obsession with the “10,000 hours approach” to an early and specialized career skill set, we are losing the ability to operate in the messy, but necessary, interstitial world — the spaces between specialties where boundaries blend, dots connect and teams work.

It’s here, amid the messy gray area, that the abilities of misfits, rebels, the nonlinear and marginalized contributors excel and add tremendous value. The lived experiences of those who have been forced to forge their own paths and to operate simultaneously in multiple worlds constitute pockets of gold to teams. Those colleagues accustomed to embracing the fuzzy bits arrive pre-armed to help others navigate — as I know, because I am one.

Other thought leaders have helped define a great team as having three core factors: diversity in every aspect; a strong culture of candor and respectful discourse; and a high degree of trust. To this list, I propose an addition: the more misfits, the better.

Fragile Monocultures. Misfit Antidotes

In an ever-changing, ever-challenging world context, diverse teams have become a requirement for survival. Monocultures die. Suddenly. Science tells us that the more similar we are, the more susceptible we are to rapid widespread destruction. And at an alarming rate, late capitalism has become an increasingly concentrated monoculture. Biodiversity, the resistance to homogeneity — a catalyst for resilience — is critical for adaptation and evolution. We know this from nature, and now for business.

“The only constant is change.” - Heraclitus

I daresay that the misfit is the anomaly, or self-selecting adaptation is the very thing that might just help capitalism survive. Misfits are no longer something to be tolerated but celebrated and embraced. We are the future.

Fellow misfits, this is my call to arms. Don your freak flag and let it fly, for this is a time of courage. Your services are needed. Whichever corner of the universe you’ve been relegated to, it’s time to stand up and say the bold, “crazy” thing again (and maybe again and again). Be noisy and do not let the fear of rejection get in the way of the greater dangers of sameness and groupthink.

To those of us comfortable within the monoculture, my request is that we recognize ourselves and listen more carefully to those on the fringes. Before we scoff at the off-the-wall-idea, let’s remember this: Every successful innovation was once viewed as stupid, crazy or impossible until it was proven successful.

The Opportunity for Our Industry

Creators, designers, architects, engineers and construction professionals: We have a massive opportunity within our grasp — to save the world, in short — and I welcome your ideas and feedback. We’re tasked with and funded by the current administration to build the infrastructure to support the next era of our country. How can we do it well?

While some of us wear our nonconformities more proudly than others, I’ve found there’s a little bit of misfit in all of us. Our differences should be celebrated. When they are, we will create environments where everyone feels safe to say what’s wrong so we can work together to get it right.

As we try to remedy the kind of encounters with which this essay began, let’s keep two things in mind:

“We” are not comparable, “we” are better.

“They” includes all of us.

Ella Hazard, RA, NCARB, LEED AP, is managing director of Arktura Ventures, Armstrong World Industries venture studio exploring new solutions in architecture, design, engineering and construction.

FOOTNOTES:

1 Oriane Georgeac and Aneeta Rattan, “Stop Making the Business Case for

Diversity,” Harvard Business Review, June 15, 2022. Source

link

2 Erin Meyer, The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business (New York: Public Affairs, 2014).