When Worlds Collide

by Michael LeFevre

Managing Editor, DesignIntelligence

September 21, 2022

As world-builders — creators of real and imaginary environments — are we prepared to lead when conflict occurs?

Sci-FI Influences

In the Cold War era of my childhood, cinematic and literary themes were dominated by the inescapable fear of the unknown. Much of this artistic angst stemmed from the ever-present threat of nuclear war. After all, the world as we knew it in the 1950s and ‘60s was only a decade and a half removed from the horrors of the first deployment of nuclear weaponry at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II. The use of such radical measures was rationalized to stop the spread of totalitarian regimes that threatened American security, ideals and life as we knew it.

Beyond real wars, the era’s storytellers were obsessed with scenarios such as gargantuan ants resulting from nuclear fallout and alien invasions — outcomes extrapolated by visionaries from the U.S.-Russia conflicts and space race. “The Andromeda Strain,” “Them,” “Failsafe” and “The Day the Earth Stood Still” are quintessential examples of such films of the day. Each featured ray-gun-zapping spacemen or monstrous mutants resulting from radiation exposure. Each represented the zeitgeist in its own sci-fi interpretation. Even the weekly network series that played to first-generation TV watchers included sci-fi stalwarts such as “The Twilight Zone,” with it’s ironic 30-minute morality tales. “The Outer Limits” and “One Step Beyond” were followed by “Star Trek” and its leadership lessons for legions of devout followers.

These Days

These days we use ray guns of a different kind. Through tweets, Dick Tracy wristwatch cell phones, the internet, glowing screens and an untold multiverse of media sources, we emit signals at unimaginable, indigestible levels. Some are for good; some are for evil. All have an impact on shaping new worlds of belief, right and wrong.

In our design firms, we’ve abandoned pencils and hand drawing in favor of digital models, handheld devices, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, laser scanners and drones. Like spacemen and giant ants, it’s enough to frighten timid souls. But despite the self-fulfilling sci-fi prophecy of space age tools coming into everyday life and practice, leaders are still required.

And what a relief it has been in my six decades of life since the 1960s to see the apparent dissolution of the Cold War and the failure of even a single alien or gigantic ant to wreak havoc on our planet. But in place of these worries have come a new raft of concerns. Terrorism is a peripatetic threat. Vladimir Putin’s March 2022 invasion of Ukraine strikes a familiar chord, even to the point of threatening nuclear action. The COVID-19 pandemic, economic and environmental crises and still-rampant inequity in social diversity fill the minds of design and other industry leaders these days. As global citizens, we are aware of and care about worldwide geopolitical issues, but most of us are fortunate enough to have to cope only with smaller-scale issues. At least, we think that’s the case. Could we be wrong?

Nonetheless, we are world builders each and all. In our everyday machinations among our new digital design tools and complex global contexts, we are asked to draw upon new levels of composure and leadership to guide our teams and followers. Acknowledging this yoke of responsibility, how can we leverage it to exert ever-greater influence and impact on those we serve? Certainly not by constructing pseudo, house-of-cards worlds based on flawed values. Rather, it will demand our waking up to a larger view that transcends the myopic singular perspectives of ego, aesthetics, profit or other self-focused pursuits.

Fabrications

In his epic book, “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind,” Yuval Noah Harari explains the fabricated constructs we rely upon each day of our lives. He calls them imagined orders. Taken for granted are world-building constructs such as money and currency exchange, clothing, religion and countless other widely accepted cultural systems that are little more than structures we’ve agreed to accept we’ve built in our quests to create civilization and social order. Christianity, democracy, capitalism? Fabricated. Consumerism, a prevailing belief system of modern life, tells us that to feel good we must consume things. We made it up. A related industry, tourism, has convinced us that we must acquire experiences to make ourselves better, richer or more fulfilled.

Per Harari, we’ve simply agreed that these things are helpful to preserve the status quo of the other belief systems we hold dearly — to keep our “worlds” going. To maintain these orders, we must never admit they are imagined. Centuries before, the agreements were markedly different. Back then, folks agreed that a cowboy could shoot anyone stealing his cattle. Thankfully, we’ve evolved. Things are a bit less life-or-death for most of us now, but still critical in different ways.

Moon Shots and World Builders

What’s the point? As inhabitants and creators of different kinds of worlds, we have duties and responsibilities to uphold them and to

continue to curate them. As leaders of design change, we are challenged to transform them for the better. As design leaders in current

practice, we would do well to survey the poise and wisdom of those who led their tribes out of the troubled times of those early nuclear-

and science-fiction-influenced eras.

JFK and the Cuban Missile Crisis come to mind. So does America’s rallying around his challenge to leverage our national hubris and

technology in executing our moon shot to explore a new world. Whether we agree that space travel is required or appropriate is not the

point. Our ability to come together at a national level to achieve a bold common goal is.

Even if we may not be individually responsible for a moon shot or dealing with Vladimir Putin (and other malevolent world forces), as leaders of our own self-shaped worlds, we are expected to prepare and lead our constituencies out of trouble in our own ways and scales, as the 1951 film “When Worlds Collide” warned us.

We all have moon shots in our own ways. In a design firm, this may mean taking a leadership position on diversity issues. It may dictate adopting a radical stance on environmental responsibility. In a business, it may suggest a product line pivot from greater profitability toward greater moral responsibility.

Why? Because we are world builders.

Subjects and Objects

For whom do we build these worlds? Ourselves, our teams, our firms or our clients? For our design or construction projects? Are these worlds real or imagined? It matters little because all physical manifestations begin with thought and are realized through cultural constructs. They are simply different kinds of created worlds. For larger contexts, consider the communities in which our works reside or the planet our projects impact.

Analysis may help us grasp the nature of the worlds we build. While world-building involves a noun and a verb — an action — peripheral adjectives and objects give each action phrase meaning. For whom? What kind? How? For how long over which time horizon? In creating any world, consider what might be thought of as “information geometry”: its width, or audience. It’s depth, or design life. It’s height, or quality expectations. Is it suitable for its purpose? And finally, the fourth dimension, time. How long will your world exist? Should it be impenetrably designed for longevity or for adaption over time?

In building design, team leaders and members bear great responsibility to contribute to the synergy and engagement of their inhabitants with the world they are creating, be it a project or a firm. Without vision and purpose, the project or world in question is doomed to mediocrity. With it, a clear concept and a strong leader, the collective can fabricate a world in which many are willing to forgo personal gains or short-term career advancement in support of the collective cause. In building their common world, one that will eventually result in a real-world building, they believe and commit to inspiring extents. In businesses outside design and construction, firm leaders carry similar mantles. While their worlds may not result in buildings, they enable those facilities with networks of goods, services and systems — worlds that support the buildings we design and build.

Our Questions

Know this: In your days as a leader, worlds will collide. With active anticipation and preparation — and a little bit of luck — you’ll be prepared for whatever ensues, even if that collision is merely a difference of opinion, a project over budget or a rift in political belief systems. Whether real or imaginary, small or large, we build worlds every minute of every day. Who will we take with us into the new lands and places we create? Do we have the skills to persuade them to join us? Are we building our worlds in the correct ways for the right reasons?

As leaders, those are our questions as we boldly go.

When worlds collide — as they inevitably will — we can only hope we’ve answered these questions thoroughly. Only then will we be prepared for the future worlds we are destined to create. If we are practiced in our deployment of wisdom, listening and perspective, we will succeed. If we have developed our abilities to discern between real and imagined worlds — the spectrum between skepticism and leadership — we will grow and prosper.

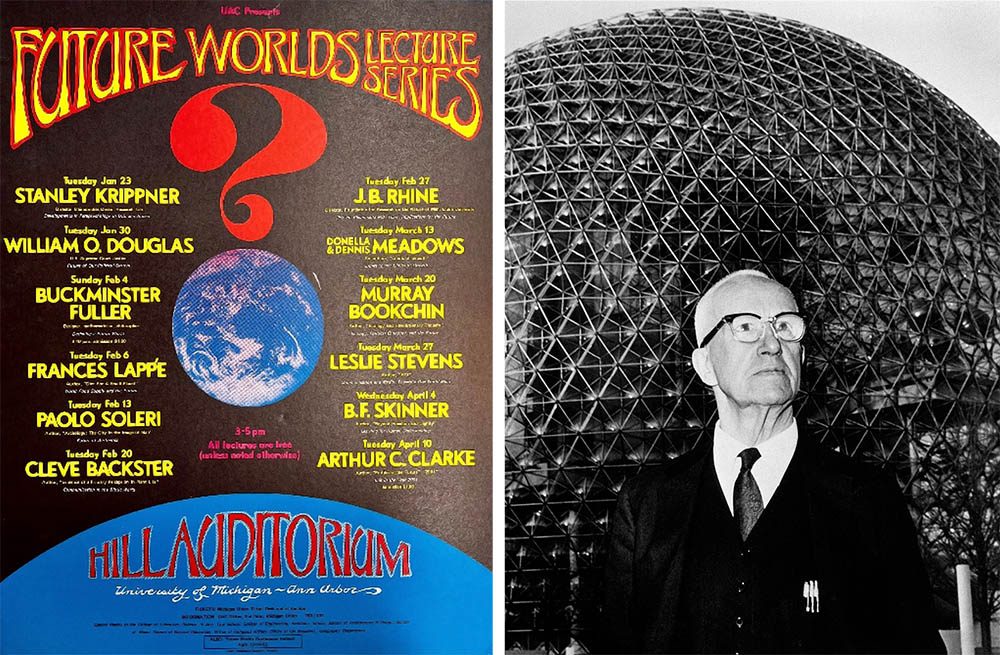

Left: Future Worlds Lecture Series Poster, Author photo

Right: R. Buckminster Fuller

A Personal Coda

In 1971, as a freshman at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, I had the great good fortune to see the legendary R. Buckminster Fuller speak at the university’s Future Worlds Lecture Series. Seated three rows from the front alongside colleagues and mentors Tivadar Balogh and Terry Sargent, I listened with rapt attention. Absorbing likely no more than 10% of what the man said, after he finished, I exited through the front left door of stately Hill Auditorium. There, as we shuffled past in the corridor, sat Mr. Fuller on a tiny black stool, a diminutive, curious, child-like figure in black glasses, humbly awaiting his next instruction, likely a car to his hotel.

Serendipitously thrust into this behind-the-scenes world to experience the reality and humility of such a legend, I struggled to comprehend the mental capacity, courage and experience he summoned to create his many worlds. Despite the respect he garnered and the admiration we gave, Mr. Fuller was, simply, a man. No more, no less. At that moment, a seemingly small, humble one. Was he that much different from the rest of us? From other leaders and followers? I doubt it. It struck me in that moment that even we listeners filing out of the auditorium possessed world-building potential. Newly buoyed by Buckminster Fuller’s theories, we now had more of it.

No matter the magnitude of our capabilities or differences, let’s try to build great worlds — together.

We owe it to one another. It’s a responsibility we bear.

Michael LeFevre, FAIA emeritus, is managing editor of DesignIntelligence Media Group Publications and principal, DesignIntelligence Strategic Advisory. His book, Managing Design: Conversations, Project Controls and Best Practices for Commercial Design and Construction Projects (Wiley, 2019) was Amazon’s #1 best-selling new release in category.