Reinventing Design Process

by Kirsten Lees

Managing Partner, Grimshaw

October 27, 2020

Interrogating the Brief, Exploring, and Embracing Differences A Conversation with Grimshaw’s Managing Partner, Kirsten Lees

Design Intelligence - Michael LeFevre (DI): Are you surviving the crises that surround us all?

Kirsten Lees (KL): We’ll always be saying we’re thriving. Or is it just surviving now?

DI: Dave Gilmore had an interesting comment recently: “Those sitting there complaining, grousing or waiting for this to be over are mistaken.” The COVID world is reality now and some version of it will be in the future. So, we better make our way and accept this in a positive way or we’re in trouble.

KL: Yes. There’s a rush to say: Let’s get it all back to how it was before. This idea that how it was before was perfect. It wasn’t. In some aspects it was better than it is now – but let’s be honest, other aspects are better now. As you say, you’ve got to continue moving onwards and upwards, grasping what you can and evolving. If you don’t, you’ll get left behind. It’s about flexibility and agility and openness to change.

DI: That’s a perfect opening comment to a discussion about reinventing. To set the stage, we’re with Kirsten Lees, Managing Partner at Grimshaw, a 40-year-old, 650-person, global practice based in London, with offices across the world in Sydney, Melbourne, New York, Los Angeles, Doha and Paris. Welcome Kirsten. Thank you for being willing to share with us.

KL: Thank you Michael. It’s great to be here. It’s an honor to be invited to contribute.

DI: : Last year, back in the days when humans were free to roam the earth, we held a conference in London. You and I sat at across from one another. The discussion was about efficiency or process and I asked you: “Are you doing any investigation or work in standardizing your process? Are you templatizing or automating things?” And you said something like, “Hold on. I hate the word process. Everything we do is a unique exploration.” Since we’re talking about reinvention, I want to open with that question. Obviously, I struck a nerve there… what did my question provoke?

KL: In a creative industry there is always a drive for efficiency and methodology that often results in the word ‘process’. And process can be so misunderstood. It’s not that we don’t have processes; of course we do. But you don’t just follow A, B, C in sequence and get fantastic architecture, products, interiors, or landscapes. The nature of our industry means it’s important to explore ideas, to have the space and the forum that can lead you to develop some areas of exploration that might not ultimately be the final output or design, but that are absolutely fundamental to shaping that.

Maybe my reaction to the word ‘process’ was that it evokes moving through a linear progression and getting to the answer. I like to call it ‘approach’ or ‘methodology’, instead. That ensures you’re deeply interrogating, rigorously challenging, and opening a collective forum that sets the framework for exploration. But exploration isn’t the only thing. It is about making sure the project has strong leadership and directionality, so it ends in a high-quality, meaningful result everyone buys into. Ultimately, it’s about producing an outcome better than we all anticipated. So, you did touch a nerve there, probably because of having had lots of internal conversations about this over the years.

DI: Those who have never been through design school or practiced design, despite working with us (and with us telling them), don’t understand the nature of design exploration; that you go down some likely wrong paths. There’s a famous T.S. Eliot quote about arriving back to the same place and knowing it for the first time. Until you went down that path or around that circle, you didn’t know. In your recent podcast with Owen Wainhouse on Architectural Masters, you talked about management and design. What’s your take on those terms?

KL: The two come together because design needs to be managed. And there’s an approach or a process in there, too. But that process needs to allow for a design to ultimately be the best it can be; to allow for exploration. What I see within the industry now – because we live in such an image-heavy, outcomes-driven, sped-up world – is frustration that we’re trying to get to the answers before we’ve had the time to challenge if the questions are right themselves.

DI: Eventually we must turn the corner and begin to converge on a solution. What I love about your work, despite being large-scale – transportation, infrastructure, sports and urban projects – is that there’s always craft. There’s an expression of humanity or poetry to your architecture that’s not the faceless, corporate, or institutional outcome it could be. In your work, craft and the hand of humans are present. I’d like to understand how you achieve that, by understanding more about your design process.

Let’s talk about the mechanics of your explorative approach. Since every project is different, how do the paths to be explored manifest and prioritize themselves? One might be driven by its site, one by its materials, and one by its historic context. How do you begin?

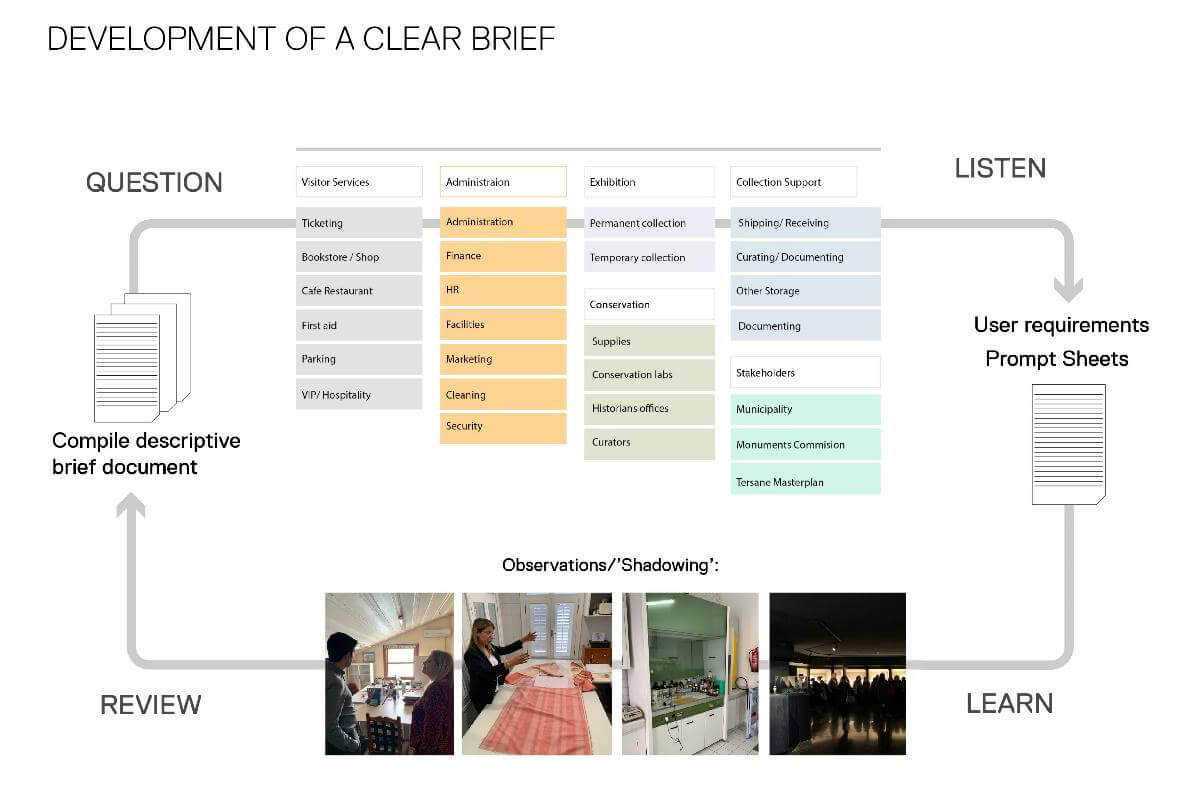

KL: People in every sort of practice work in their own way. So, I speak very much from personal and Grimshaw points of view. How do we start? Something we intrinsically value is that we start by not drawing anything; we start by asking questions. We start by interrogating the brief. Understanding what it is we’re trying to achieve and who will use the building, who is going to be part of creating the building and master plan.

I remember one – an energy-from-waste project. Normally, the nature of this typology is that these projects are often delivered within the construction company as a turnkey project. In this instance, the specific location was very sensitive, and they felt, “Oh, for this one we need services of an architect to help us with.” And so, they brought us in expecting us to just get on with making the facades pretty.

We started by asking, “What’s the process?” “Well, you don’t really need to know the process” was the response! We said we did because we needed to understand what parts of the building had to go together, where the adjacencies were, what bits we had got to play with in terms of creating the massing; could this be dislocated from this component because that’s what makes the composition? And what size are the trucks? “Why are you asking these questions, why do you need to know the size of the trucks?” they said.

That project in Suffolk has become SUEZ’s flagship Energy from Waste power facility. It became that not because we were brought in to do a nice façade – which is what they expected of us – but because we developed a relationship and an understanding among ourselves, SUEZ, the council, and the community about what we were trying to achieve. Obviously, we needed to achieve an efficient engineering plant. But we also wanted to break down the perception that energy from waste is basically burning rubbish. We wanted to intervene and improve upon this sort of big, scary, horrible thing you don’t want in your backyard.

By asking all these questions we delivered a design that was very efficient to use and delivered on the objectives we set for the project, and beyond. We delivered a building that is loved by its community and its users, that gives back in a way they hadn’t anticipated. Questions are fundamental – understanding the brief and getting to a point where there’s an understanding of the task and the challenge we’re trying to resolve.

Building from that shared point of understanding, we then start from the site, the use, and look strategically at big moves that start to put in place a series of principles. Then the design evolves around those principles. But it’s about those big, early, key moves and establishing the principles everyone can buy into. That is how we avoid flip-flopping or changing the design. It continues to build and evolve to develop and enrich the original principles, but you need to set those in place first.

DI: You called it: “interrogating the brief” or asking the right questions. For most of my career, what we were typically given as a program in the US was a little more “I need a 100,000 square foot building and it’s got to cost 30 million dollars. That’s all we know. We don’t do this for a living. You’re the experts”.

I just read Broken Glass, a book about Mies van der Rohe and the Farnsworth House. For so many of architecture’s iconic buildings, it was all about the making of the thing. Forget the program or asking questions. Forget the client, whether it leaked, or if the air conditioning functioned. In Mies’ case he got basically no program, just “design a country house”. He certainly never interrogated the program or reached common goals with his client. It was simply his art, his creation.

Now, in a more complex world with more regulatory, social and environmental issues, you’re addressing those forces in a deeper way. In some instances, you run the risk of alienating your clients when they ask: Why are you asking me these questions? In some cases, such questions can come up with scary answers. Like, do we need to build this building at all? Or what is its impact on society? Have you had those experiences?

KL: Asking questions initially throws the client, because they won’t be expecting it. They expect us to simply go away and come back with a product. We believe passionately that our buildings need to work for the users, and therefore we need to understand everything about them, the community and even the users beyond the immediate use of the building. Buildings must have a longevity and a flexibility to outlive their immediate use; therefore, you need to be thinking about that in advance.

So, we try to really impress the importance of questioning. In the example I gave – SUEZ Suffolk – we initially asked some questions and the client didn’t understand why we were asking them. But at the end, they really appreciated the journey we all went on. Not every client has the same level of understanding in delivering buildings. Why should they? Because often that is not their training or background. But in developing a building for people to use ultimately, it is a very close collaboration between the project team. It’s fundamental that the client understands that they have an important role in developing that. What clients appreciate about the way that we work with them is not that we need all these answers and sit back. It’s that we assist them and take them through the impact of the decisions and the different directions that projects can take on that basis.

DI: So many clients are not skilled with writing programs and don’t understand why you’re asking these questions. They’re not expert in what we do as designers and builders and are uncomfortable with design process. They say: “I don’t have time for this planning and dialog”. But insisting they do it builds common goals. Then, when you’re on the journey together, you don’t find out half way through that they wanted to get this building done and sell it in a year, and you wanted to do the most sustainable building on planet earth to own long-term. Too many people mistakenly think they don’t have time for questioning and goal setting.

KL: Every project is different. Depending on the scale – on infrastructure projects for example – clients aren’t always involved in the end use of the building. So, we’ve got to tailor methodology to the project circumstances. But we’re very clear with our clients that we need a strong brief. If they don’t have one in place when we’re appointed, we assist them in developing a brief because it’s sets out key goals and questions. To your point earlier, do we even need a building? Is this the best idea for this location?

I read an article the other day where this old practitioner had been approached by a client with a stunning, beautiful site and he wanted an individual house. Ultimately, he persuaded the client they shouldn’t build a building there because the impact on the environment would be detrimental. To your point earlier, there is a perception and maybe it’s come from historical examples whereby architects sometimes are perceived as people obsessed by their own vision and the output and the product: “To hell with the brief and the client! They’re not important, it’s the architects’ vision”. We’re almost the antithesis of this. We’re about realizing the client’s vision.

We bring huge amount of skill and experience and professionalism and creativity and we’re very proud of what we can contribute to that. But ultimately, it must be about a shared vision – one we can all invest in.

DI: How is a typical design team organized? I’m assuming it’s not one individual sitting off in a corner having their “vision”. Are some more expert at the brief and programing process? And others whose responsibility is design?

KL: One thing we’re immensely proud of comes from the ethos and culture that Sir Nicholas Grimshaw established – that good ideas can come from everyone. We operate a flat structure with no hierarchy or monopoly on ideas. We think it’s important that everyone feels they can speak up and contribute ideas, obviously, with different levels of experience. We also believe that craft – how things go together – is similarly important. You need to understand the process of making.

As a result, we have never organized our teams into specialists – some practices have a competition team, a design development team, a construction team. We’re integrated because we think it’s important that everyone has experience of every stage of the design process. Because if you don’t understand what you’re drawing on paper and the implications of that on site, you’ll never really, fundamentally understand it. After you’ve been poring over drawings that line up perfectly, and then you’re onsite and you see the way they chuck concrete into formwork… they’re just worlds apart. You need to understand that.

There are different parts of our project teams. They will grow and some individuals aren’t able to stay with projects all the way through. But there’s a core set of individuals with any project from start to finish. With architecture, you never know everything and you’re constantly learning. So, it’s important that everyone can question, learn and contribute. Every project has a partner in charge and we always have a project architect. That’s a critical role within any project because in many ways, as the holder of all the information, and the vision. They interface with the client, the design and consultant teams. Depending on the scale, you can have three, four, or ten project architects responsible for different areas. They’re the holder of all knowledge and coordinate pulling everything together because there are so many strands, so many decisions. It’s important that it’s brought together in a cohesive way.

We always have a combination of architects at different levels of their career, to bring different levels of experience. Depending on the project we may include urban designers and industrial designers within our team. We think it’s valuable to develop our specifications in-house, so we have a team that helps with that. The design team write the specifications so we’re very familiar with the details of the building with assistance and guidance from our specs team. Essentially, we’re writing our specifications ourselves through a process that builds on experience using a system that ensures the level of quality.

DI: Where does design responsibility fall? Is that the partner, a separate project designer, or is that the project architect? And management? Do you have those designer and manager roles?

KL: Yes, but again it comes down to project scale. You can’t separate design and management because you need to be aware of the program within which you’re designing and pull together all the inputs and consult at the right time. It’s important that every member of the team is aware of traditional management aspects. Every member of the team also contributes to the design. No, we don’t have a designer sitting in the corner developing design sketches and then instructing others to develop that in service of their vision. The vision is developed creatively and collaboratively between the team and the partners. The partner’s role and experience is very much about providing strategic direction, being part of the design decisions. You’re making hundreds of decisions all the way through, but they build to points where you need to make larger decisions and so making them well is important.

At Grimshaw, we offer a lot of partner time to projects and to clients. We’re not just figureheads. We don’t just win the project and then move on to the next one. All the partners in our organization are intimately involved in leading their projects, in terms of managing the client relationship and managing the design process, and then managing and leading the design and contributing creatively to it. But that doesn’t mean to say we undervalue the huge creative contributions of the project architect and team.

Even where you have tasks broken down and performed by different individuals, it’s still vitally important that you get the right level of knowledge and communication. We don’t have a separate project management team saying, “you need to meet this deadline”. If you don’t have all the information you need you can’t make that date. So, you have to manage yourselves to get it. You can’t coordinate a design if you haven’t got anything to coordinate. Even where we have identified project managers on a project team, they’re embedded in the team structure and not a separate group.

DI: Let’s talk about the “management-design continuum”. You made a comment on your podcast that you’re the managing partner now, but you didn’t necessarily go to school for that or necessarily have the skills to manage anything. In architecture, it seems very few of us do. We went to school to learn to make things. Had we been good managers, we would have been managers or bankers. One of the biggest things we fail to manage is the cost of our projects. Too often, architects have this reputation, perhaps deservedly, “We are going to blow the budget and it’s going to be beautiful, client be damned”. We see it as our responsibility to push the edge and use innovative materials. Blowing the budget seems an almost inevitable result. In the US, we have design-bid-build-delivery, but for most of my career, I worked under a CM-at-risk delivery method. That brought cost accountability to the team. In the UK you have quantity surveyors and cost estimating. Has that shaped how you go about your design journey? Is it positive? Does it keep you in check or do you still have the inevitable rollercoaster ride which causes design rework and dilution?

KL: I think architects are great generalists in a world of specialization. Everything has gotten more complex, everything is being subdivided. One of our prime roles beyond developing the design and the creative vision for a building is about coordinating all the inputs from all the other parties. That includes the engineering team, the client and a huge number of other people contributing to creating the building. Any architect that doesn’t have a strong relationship and open communication with the core consultants isn’t doing their role. The reasons for a building going over budget is often about design process itself: the design gets developed and everything gets refined and fine-tuned as the design progresses.

But the way the design process works is that the cost consultant is always a few steps behind (this can be anything from three to six weeks behind) and schedules typically don’t allow enough time to recognize that. They need that time for doing the estimate. Then we evaluate. What decisions led to this and why did it deviate from before? And then what should follow is a period of alignment and correlations. So often, because a programme is seen to be driving everything, it creates a schedule disconnect. It takes time and effort to coordinate design, and then suddenly, you make all these crazy, fast-paced decisions about cost without the same focused and detailed level of consideration. That’s where a lot of conflicts, misconceptions and errors come in.

DI: I’d certainly rather spend that time upfront aligning the goals and controlling cost along the way than doing the frenetic rework process you just described.

KL: Agreed.

DI: On the other side of the spectrum from this issue of cost and convergence, you’ve got incredible divergence within your firm. You’ve got people that speak 55 languages in cities around the world. How do you manage and embrace and translate that to result in richer, more diverse thought, input and work? I spent the last 20 years of my career just translating between owners, architects, and contractors - and we all spoke English. How do you cope with that diversity and number of cultures and languages?

KL: We work all over the world, but our buildings are for local communities. They are shaped by and need to respond to their context but have to reflect the needs of the people that use them. We fundamentally believe that having a diverse and broad range of experience that contributes to design makes for a richer process and building. Generally, we speak English as the common language. It’s the world language, but we do have many people on our teams – and 55 different languages. There’s no one person that speaks them all though!

But so many people do speak four or five. I’m so impressed. How do you do that? I joined the practice because I was a Spanish speaker. The firm just won a project in Spain and was looking for a Spanish speaker. But as you rightly said, language isn’t just about language. There are so many components to it.

For example, we were doing an art gallery in north-west Spain and between the Spanish contractor, a British architect, and an Austrian specialist façade engineer, there were all sorts of cultural differences and approaches. The Spanish like to resolve more things on site than the Austrians or even the British. With the northern Europeans there’s more pre-planning. What I find fascinating about it was that it started off as condemnation and misunderstandings. I remember the Spanish contractor complaining about the façade specialist: “They’re asking about every single millimeter! They’re just planning away and fretting over every millimeter and they’re charging us for this tolerance and saying we’re out of tolerance. They’re just planning. It’s all about planning”.

So yes, there was a long period of planning and preparation of schedules and shop drawings. Then the Austrian contractor arrived on site and within a matter of weeks their element was complete. Then, the Spanish contractor’s view was: “This is incredible. They come in and it’s like Mecano. It all goes up perfectly. It’s just done, clean, and they’re gone”. For those sorts of initial misunderstandings and cultural differences to move to absolute appreciation taught us all a new kind of respect for different approaches.

We also had a resident engineer from the façade contractor on site. What they valued from the Spanish side was their flexibility. The attitude of working together to solve a problem because – let’s face it – there are always unknown elements and surprises on site. The flexibility to do that without rancor or recrimination offered real value. Moving from oppositional miscomprehension to come to view and respect each other is a tiny example of the value of the rich, diverse workforce we have at Grimshaw, on our projects and how quality results.

DI: So, a healthy respect, tolerance, and empathy for diverse cultures and others’ processes are an integral part of your approach. I love that discussion of the cultural side. But I wonder, in a practice in which you’re reinventing the design process every time, working in dozens of locations all around the world with 55 languages, how do you achieve consistency and quality? Are there rules, guidelines or procedures, or do you just rely on good old-fashioned human judgment and experience to ensure that projects don’t go off the rails?

KL: It’s wrong to say we don’t have a process. We do. We have an approach and methodology, but it needs to align and adjust to the circumstance of the project. We develop the brief. We challenge and share the design as it evolves with the client and by working closely with the wider design team and other specialists including engineers, acousticians, lighting, landscape, etc.

The methodology is about communicating regularly and frequently and having a direction; always coming to conclusions developed through consensus, then built on and believed in. Maintaining a program of continual consistent improvement and refinement is the framework for achieving quality in projects that are very different. We don’t have a style book we draw from. We approach every project from first principles. They’re consistent in their level of rigor, interrogation, and quality of output. It’s a method which has been fine-tuned over years that is applicable to every project – the cornerstone of excellent output.

DI: : In your process of continual reinvention, what will your next reinvention look like? Have you had to reinvent your process for COVID? And what do you see beyond that?

KL: Obviously, we’ve gone through the impact of the pandemic. In our attitude and approach, it’s important to be open to change. So, we’ve embraced change positively but not blindly. For example, last year we spent time looking for new premises. Our London studio had grown beyond the confines of the space. We had two satellite studios five minutes from the office, but it still created a sense that not everyone was together. Then there was the COVID lockdown and the move from being within one place, which was our aspiration, to being in 270 different places. The sense of communication became even more important now that we collaborate via the medium of Zoom. Do we all love Zoom? No

But it gave us pause. Now we’ve thought about how it will be when we return to the office. We’ve seen the benefits of working from home. We did surveys last year to understand what people were looking for in a future office and what the office means to them culturally, socially, and functionally – to allow them to do their job. We got lots of feedback and found that some elements of the office didn’t work. We’ve also done surveys of people working remotely, intensely, doing highly focused tasks. Having environments where you can focus has been productive and beneficial. But what everyone is missing is the contact, the interaction, and collaboration. Sure, we found ways to collaborate technically, but we’re human animals and we need that contact. That led us to rethink what the office is and what its fundamental function is. Clearly this virus is still with us and is likely to be with us for some time. We still are not returning to the full office because of social distancing, but we’ll look at it differently when we do.

Over the summer we reconfigured the office. We haven’t sought to recreate the traditional office with some individual desks with fixed workstations, but socially distanced. We’ve identified some areas within the office and said: let’s look at these in a completely different way. Let’s create what we say we all miss about the office environment, the opportunity to meet as a group and collaborate over a desk. Not a desk with a series of screens on it, but a desk where you can see your fellow colleagues and share. To lay out a big drawing and sketch over it is a fantastic means to collaborate. We’ve also provided a long space to pin up and showcase our projects.

So, we’ve created two areas we’re actively encouraging people to trial out and move and shape as they require. To shift, try out, explore and experiment to see if that helps us collaborate in a different way. Home working is with us to stay, so we’ll need to find a balance in the future. Maybe the purpose of a studio is more about when we come together. How can we make that intense, interactive, productive, and collaborative? That’s what we’re trying out right now – our approach to current circumstances. Beyond that, we’ll continue to explore.

DI: That’s a fitting conclusion to a discussion about reinvention: you’re in the middle of reinventing as we speak and will continue to be. Despite a difficult subject to understand and talk about, you’ve illuminated how you’re reinventing your process on each project. You have a wonderful way of making your work client-and-user focused, and project-unique – the kind of work that invokes the best out of professionals doing what they love.

Thank you.

KL: It’s been a fascinating and fantastic interlude to think about these things.

Kirsten Lees is Grimshaw’s London studio’s Managing Partner, overseeing the development of the studio as it continues to grow. Kirsten is a highly experienced architect with over 25 years’ experience in architecture, strategic planning, urban design and regeneration in sensitive environments within the arts, sports and master planning sectors. She brings insight and creativity to the development of strategic projects and demonstrates strong conceptual judgment when integrating buildings into sensitive urban and rural settings.

Genuine innovation and architectural distinction distinguish Kirsten’s projects, which are founded on the insightful translation of client and stakeholder objectives. Her work has been acknowledged for its subtle response to place, the pre-eminence of the cultural agenda, and its unique expressive and material qualities. She was shortlisted for the AJ Woman Architect of the Year award in 2014 and is currently shortlisted for the BD Architectural Leader of the Year 2020.