Redefining the Profession

by George Johnston

Professor of Architecture at Georgia Tech and Principal of Johnston+Dumais

In his new book, “Assembling the Architect”, author, historian, and professor George Johnston draws from the past to suggest future directions. An interview.

DesignIntelligence (DI): George, your new book focuses on defining the history and development of the profession, the journey to its present state. In light of recent events, and consistent with DI’s future-focused mission and current theme, what do you consider some of the changing conditions that are compelling us to redefine the profession?

George Johnston (GJ): The acceleration and confluence of recent events demonstrate how intertwined the profession is with the world – economically, environmentally, socially, technologically. As if architectural practices didn’t already face enough challenges from ever-tightening constraints and expanding expectations, now they must add the urgency of a global health pandemic and the lingering wounds of social injustice to the weight of existential concerns the profession must bear.

Like so many institutions, the profession of architecture and architectural education are being challenged to account for their past, for their parts in perpetuating inequitable and exploitative systems and approaches. But, it’ s difficult to soberly reflect on such matters in the midst of a crisis; to chart a path ahead when the next payroll is in jeopardy, when livelihoods and even lives may be at stake.

DI: How would you suggest the profession go about addressing these challenges?

GJ: The role and responsibility of the historian is to help put current challenges into some framework with respect to the accumulated concerns and preoccupations of the past. That won’t necessarily give us a precise roadmap for future action, but it can be helpful for understanding some of the precipitating causes of the crises at hand. This in-turn may help us be more circumspect about the unintended consequences our best-meaning actions might entail. And being so informed can keep us alert to any future possibilities suggested by the patterns of the past. That’s some of what I hope my work contributes in charting the history of architectural practice.

DI: What historical patterns should we be more aware of today as we think about the future of the profession?

GJ: My recent book, “Assembling the Architect”, and an earlier book “Drafting Culture”, deal with what I consider to be some of the perennial structural paradoxes of US architectural practice, ones I trace back a century-and-a-half to the period of national recovery and expansion following the Civil War. That period was when the profession of architecture in the US was being defined as a distinct vocation separate from either its dilettante-designer or artisan-builder beginnings.

Within a relatively short span of decades, the field of architecture was transformed by an increasingly activist and protectionist professional organization, the adoption of university-based architectural education, the rise of general contracting, the embrace of the design-bid-build delivery system, and state licensure of architects. One of the unanticipated effects of all these profession-building efforts was the narrowing scope of the architect’s role as compared to earlier times when neither the title nor the functions of architect had been so strictly fixed. The ironic result of the architect’s elevated status as owner’s agent was a gradual distancing from the construction site, from the interplay of capital and labor.

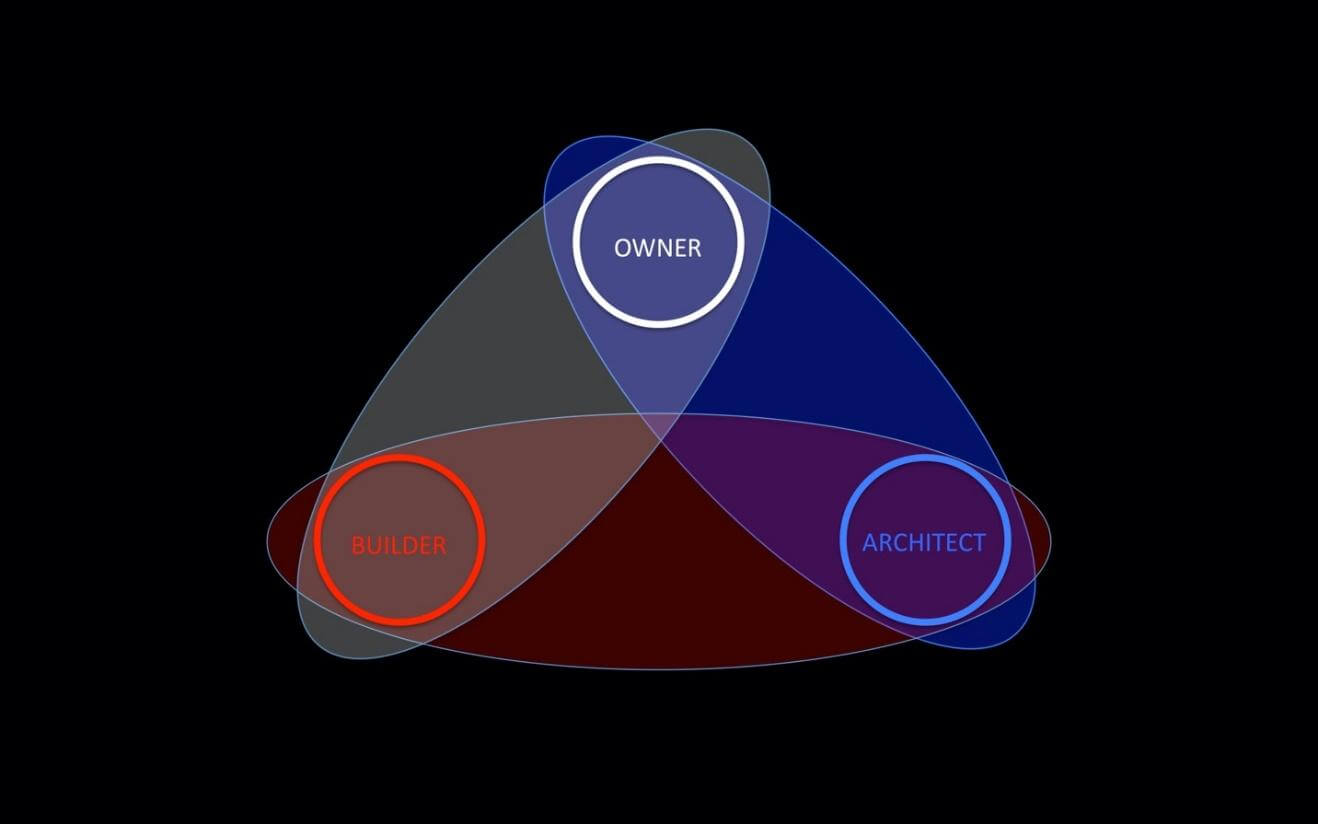

DI: You write about the A-O-C trinity we first learn about in school, the relationship between and among the architect, owner, and contractor. Is this simple three-party division at the root of the issues we face as a “profession”?

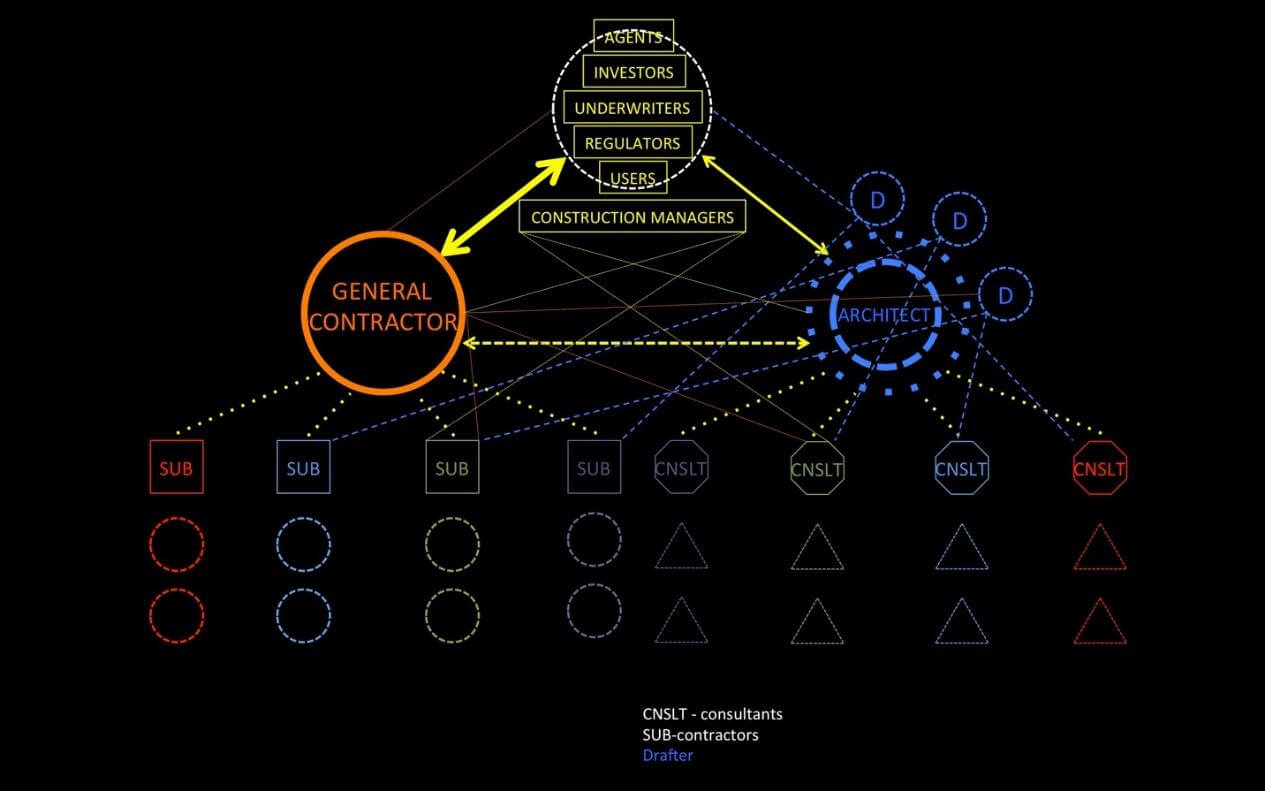

GJ: I do think there is a disconnect between the elegance of that

triangular diagram and the potential complexity of the actual organization of a project. Each one of those three entities is really a multitude of actors, each with competing aims and interests even within their own respective “silos.” Historically, there was a greater fluidity among the different players than we came to assume over the course of the 20th century.

The essential relationship, however, is still the one that pertains between an owner who needs a building and a builder with the requisite skills and a crew. An architect could emerge from either side of that equation, as an owner providing their own designs or as a masonry or carpentry contractor employing a drafter to produce drawings in-house for planning and estimating purposes. Hybrid formations were always a possibility.

Indeed, before the emergence of general contractors in the late 19th century, architects themselves were likely to perform many aspects of that integral role as part of their standard services. It is ironic to recognize in taking on that role, general contractors were compensated for a service for which architects had never been able to command an adequate fee. That’s a longer story, but one that holds many lessons with regard to the financial structure of the profession.

DI: As the profession evolved with society, an infinite number of roles and blurred relationships took form. Just within the role of architect there are thousands of variations, interests, and practice areas. We could list the designer, spec writer, production architect, manager, BIM leader, and so on, but the public simply says “architect.”

GJ: Exactly! What I see today in the proliferation of project delivery methods – the developer-architect, the design-builder, specialized design assistants, various construction management approaches, integrated project delivery and the like - is not so much a direct challenge to dominant design-bid-build modalities as a return to pre-modern norms, a more generous, inclusive tradition that embraced a multitude of alternative possibilities and blurred roles. The digital tools we have at our disposal today can perhaps empower many more diverse approaches than current regulatory and professional strictures can comfortably fathom or allow.

DI: Has the broad range and plurality of architectural duties contributed to a slowed maturation or a diminished stature of the profession? Is the profession of architecture misunderstood or maladapted because it’s in fact, dozens of professions?

GJ: There is a vexing paradox in all this. To raise the stature of the profession from what was admittedly a rather suspect vocation - one subject to all manners of financial and material malfeasance - a relatively small cadre of paternalist practitioners successfully advocated for state-sanctioned restrictions on the use of the title “architect.” While one might agree that such profession-building efforts succeeded in securing a market and in establishing a strong public profile of ethics-bound service, we must also recognize that such restrictive claims to the title excluded many whose work was architecture in-effect, even if not sanctioned by a title. If we look more closely, we are likely to find cases where such protectionism was also a mechanism of privilege and systemic exclusion based in unacknowledged gender-, race-, and class-based biases.

The profession really spent the last century and a half defending claims to a narrowing title rather than expanding its inventory of applicable expertise; by limiting access rather than redefining the field’s social purpose. In laying claim to a very small subset of edifying purposes, the profession of architecture has necessarily ceded authority to other fields – city planning, civil engineering, landscape architecture, urban design, interior design – for the constitution of the architecture of the public domain. Firms may gather several of those disciplines under their umbrella, but this only confirms that as it is practiced today, architecture is a specialization within the larger design and construction continuum, one within which even more sub-specialties pertain.

At the same time, unfettered use of the term “architecture” has absolutely exploded in non-building fields such as computer science, electrical engineering, bioengineering, and many others. It’s in this sense that I think that the concept of “architecture” has become a pervasive social and technological concept, the signifier of a complex, locally situated, globally integrated system of structured and virtual relations with both discernable and undiscernible effects. Obviously, no state-issued architect’s seal can exert dominion over all of that!

DI: Are you suggesting the profession be de-regulated? That claims to the title “architect” be opened-up? In “The Future of the Professions”, the Susskinds pose a future in which routinized tasks will be outsourced. They speculate the end of architectural practitioners as we know them. What’s your take?

GJ: We are talking about the future, right? We have to question whether the current professional regulatory system, born out of 19th century motives, is still adequate to meet demands likely to emerge in the next decades of the 21st century. Professional licensure was only one mechanism among many others intended to safeguard the health, safety, and welfare of the public. Even then, only a small proportion of our designed and built environment ever saw the shadow of a licensed architect’s hand.

Over the course of the 20th century, the design and construction enterprise became highly integrated through adoption of state and municipal zoning ordinances, public planning processes, uniform building codes, energy codes, accessibility and egress requirements, stormwater management and other environmental requirements, and so on. For each of these, established procedures of submittal and review were initiated by a variety of parties, to ensure conformance and enforcement, and to petition for variances and exceptions. These rules of the road are constantly being refined to reflect adjustments in public policy and a general ratcheting of standards as we get more precise in specifying desirable performance outcomes. It is easy to see the contractual centrality of the architect as a mediating agent, and the disproportionate liability that conceit has historically entailed, are anachronistic propositions! In addition to the public regulation of design and building, consider the multi-disciplinary expertise needed to address any complex problem, the increasing integration of digital design and fabrication technologies, the contingencies of material production processes, and the pressures of supply-chain logistics and cost control. Perhaps less easy to model are the intertwined nature of public and private interest, the dignity of labor, or the vicissitudes of human desire. But each of these rule sets is potentially translatable into so many algorithmic descriptions and manipulable parametric scripts for computing variable combinations and design alternatives.

Some would like to imagine machine learning will enable the rise of a new breed of “master builder,” architects re-empowered by an all-encompassing system of digital command-and-control. I think that is a fantasy founded upon dreams of the Middle Ages. Rather than a romantic return to some mythologized past or the fiction of creative autonomy, I’d rather anticipate an expanding field of many coordinated actors, all interacting with empathy as agents of their own expertise, enabled by a retinue of tools and applications that automate and facilitate their tasks and link their work to the work of others. This is the sort of disaggregation and democratization of professional roles that I think the Susskinds have in mind.

I don’t suppose the need for an architect’s design authorship would simply disappear or be absorbed into an all-encompassing automated building factory. Rather, the demand for bespoke architectural services we courted and depended upon in the past, in service to wealth and power, would be only one possibility among a host of hybrid models. The roles of architect, owner, and builder may become more fluid again, able to variably recombine the functions of project initiation, design negotiation, and construction realization necessary to accommodate the myriad designing-and-building purposes for which only architecture – in that broadened sense suggested earlier – can meet the demand. One question this raises, however, is whether all individuals will need to be educated in the mold of the generalist, licensable architect that we have assumed for just over a century as the operative default.

DI: I’m glad you mentioned the role of education. As a scholar of the history of the profession - and an educator - you’re in a unique position to affect the course of things. Are you doing anything to catalyze change in the next generation of practitioners?

GJ: Well, I hope I am having an impact, pressing at disciplinary boundaries even while working within the system we already have. I recognize I’m probably a part of the very problems I’m trying to describe. The research I undertake is a means of questioning my own assumptions. I try to challenge uncritical acceptance of the paradoxes of practice as if they were laws set in stone – and to help remedy any historical amnesia about how those paradoxes were formed. I try to suggest that any challenge to received or conventional wisdom requires engagement with the broader culture, and the political economy of building, rather than just focusing upon narrow disciplinary domains. As much as I love design practice and the art of architecture, I am increasingly convinced the real challenge is redesigning practice itself. We need to move beyond overly simplified models of how architecture is practiced.

If you look at schools of architecture right now, it would be wise to question the long-term implications of the large institutional investments being made in software licenses and industrial-scale CNC fabrication equipment. Architecture students are being steeped in a collaborative culture as digitally enabled makers. The particular stylistic fixations of the 19th and 20th centuries are only a vague background for exercises in modeling and performance simulation. Students are questioning how our cities get made as well as how buildings get fabricated, how public policies interact with private investment, how their labor is valued, whose interests are being served.

In coming decades, I think these emphases will result in the emergence of a variety of practice formats that broaden the definition of the architect’s role. They are likely to yield new overlaps and blurred distinctions among developer/designers and contractor/builders as has been so richly precedented in the past. This will necessitate the development of new mediating tools and open-sourced apps to facilitate the re-bundled social relations of practice. That was the kind of impetus that spawned, say, shop drawings and change orders a century ago.

For the immediate future, I think we are all challenged to make access to the profession more open to those historically excluded, to find ways to re-distribute the cost of education, and to share responsibility among all the stakeholders for this ongoing social and technological conversion. This is not the first time we’ve been challenged to redefine the profession. I’m pretty sure it will not be the last.

DI: Thanks for this history lesson, George, and for speculating about what may be over the horizon.

GJ: My pleasure.

George B. Johnston is Professor of Architecture at Georgia Tech and principal of Johnston+Dumais [architects]. He has over 40 years of

experience as an architect, educator, academic leader, and cultural historian. He teaches courses in architectural and urban design,

cultural theory, and social history of architectural practice; and his research interrogates the social, historical, and cultural

implications of making architecture in the American context. He is author of the award-winning book from The MIT Press,”Drafting Culture: A

Social History of Architectural Graphic Standards”, which has been lauded for its insights into the ongoing technological transformation of

the profession.

George holds a Ph.D., from Emory University, 2006; an M. Arch. from Rice University, 1984; and a B.Arch. from Mississippi State University in 1979.

His most recent book, “Assembling the Architect: The History and Theory of Professional Practice” (Bloomsbury, 2020) traces the formation and standardization of fundamental relationships among architects, owners, and builders and cultivates a deeper understanding of the contemporary profession. As both practicing architect and cultural historian, George is open to and supports research and design projects that involve themes of memory and modernity; institutions of cultural exhibition and display; changing design technologies and representational practices, approaches to American vernacular architecture and cultural landscape; and the critique of the everyday. Propelling his inquiries is this central concern: What recuperative role can architects’ practices play in this age of social and technological upheaval?